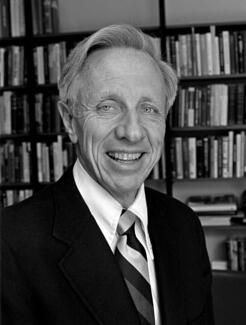

A tribute to John Grimes Linvill, 1919-2011

For leadership in education as a teacher and writer and, as an administrator, in the development of a reader for the blind based on modern electronics technology. ~NAE citation

“For leadership in education as a teacher and writer and, as an administrator, in the development of a reader for the blind based on modern electronics technology,” National Academy of Engineering (NAE) citation, 1971. |

Written by Martin E. Hellman and James Gibbons for the National Academy of Engineering (NAE).

JOHN GRIMES LINVILL, who chaired Stanford University’s Electrical Engineering Department from 1964 to 1980, died on February 19, 2011, at the age of 91.

John was a towering figure in Silicon Valley, while his soft voice and quiet demeanor traced to his roots in Missouri, where he was born on August 8, 1919.

As chair of Stanford’s Electrical Engineering Department, he oversaw its transition from a leader in vacuum tube technology to being at the center of electrical engineering’s move to solid state devices. John saw the emerging opportunities in semiconductor devices and integrated circuits earlier than most people. His foresight and leadership gave Stanford a head start over many of its peers in what was arguably the most important technology of the 20th century.

John received his bachelor’s degree in mathematics from William Jewell College in 1941 and his bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1943, 1945, and 1949.

After teaching at MIT for two years as an assistant professor, he joined Bell Labs, doing research on transistor circuit design.

Stanford Engineering Dean Frederick Terman then recruited Linvill to build a program around the application of transistors. In 1955, John became Stanford’s first appointment in a discipline that shaped an industry that, in turn, shaped the world.

Over John’s lifetime, electronic computation increased by a factor of roughly ten to the twentieth power. Probably the only other time in Earth’s history when there has been such a rapid increase in any quantity is when life first evolved. John played a key role in bringing about truly monumental changes.

Stanford’s program was influenced in 1956 with the arrival in the Bay Area of William Shockley and his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. Out of that beginning, and with some birth pangs, emerged what is now known as Silicon Valley.

John talked with Shockley about Stanford possibly building a semiconductor lab. Shockley said that Stanford needed to build a lab where doctoral students could build semiconductor devices as part of their thesis work. Shockley offered to train a person whom John would select in how to build semiconductor devices. John invited his former doctoral student James Gibbons to do that job.

Gibbons accepted and initially worked half-time as a Stanford faculty member and half-time at Shockley Semiconductor. They succeeded in setting up the first university laboratory where students could fabricate semiconductor devices, with the first device coming out of Stanford’s fabrication facility in 1958. The attached photo shows John Linvill, Jim Gibbons, and Gerald Pearson (then on leave from Bell Labs, later Professor of EE at Stanford) examining that device. Linvill and Gibbons partnership also produced their ground-breaking 1961 graduate text, Transistors and Active Circuits. Linvill had an uncanny ability to spot great talent and Gibbons later became Dean of Stanford’s School of Engineering.

In the 1970’s, as integrated circuits supplanted discrete transistors, Linvill, Gibbons, and their colleague James Meindl, founded Stanford’s Center for Integrated Systems (CIS), a partnership between electrical engineering, computer science, and industry which allowed students to fabricate integrated circuits.

CIS was built around the idea that future computing systems needed innovation in hardware, software and architecture. That vision led to Stanford having the first major university microelectronics facility. Over the next several decades, that idea spread to many of Stanford’s peer institutions.

As co-director of CIS, John helped implement a program to bring industry professionals to Stanford and that placed Stanford doctoral students in industry for a portion of their education. CIS has become the model for university-corporate partnerships.

John also played a key role in Stanford’s move into biomedical engineering. This was partly due to the his daughter, Candace, becoming blind in infancy. At that point in time, the primary reading aids for the blind were cumbersome Braille books. Linvill developed a way for Candy to read any printed material using the Optacon (optical-to-tactile converter).

This was a portable device with a small, hand-held camera that could be moved across any type of printed material to generate images on a fingertip-sized tactile display that was then interpreted by the blind reader. This allowed the blind person to not only read text, but also to “see” figures and more.

Krishna Saraswat, now Professor Emeritus of EE at Stanford, who did his Ph.D. at Stanford developing high voltage MOS transistors for driving the 144 ultrasonic pins of the Optacon, expressed the emotions that many who worked on the Optacon felt: “The joy I derived by seeing blind people being able to perceive printed material for the first time taught me an inspiring lesson for the rest of my career.”

In 1970, Linvill co-founded Telesensory Systems Inc. to market the Optacon worldwide. This device became one of the most important examples of how technology could be applied to the development of assistive devices for people with disabilities. In 1971, Industrial Research Inc. named the Optacon one of the 100 most significant products of the year. Helped by her father’s invention, Candy attended Stanford and earned a doctorate in clinical psychology.

John’s interest in biomedical engineering went far beyond the Optacon as can be seen from his hiring Al Macovski in 1972 as the first joint appointment between Stanford’s EE Department and its Medical School. This very successful effort led to a new Bioengineering Department at Stanford and many additional joint appointments.

Linvill’s influence and friendship extended to many others, including John Hennessy, founder of MIPS, President Emeritus of Stanford, and Chairman of Google’s parent Alphabet Inc.; and Jim Plummer, later dean of Stanford’s School of Engineering.

Among his many honors, Linvill was named a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in 1960; was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1971; was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1974; received the IEEE Education Medal in 1976; received the John Scott Award in 1980 for his work on the Optacon; received the American Electronics Association’s Medal of Achievement in 1983; and received the Louis Braille Prize from the Deutscher Blindenverband in 1984 for the invention of the Optacon.

John was survived by his wife Marjorie Linvill, his son Greg Linvill, his daughter Candace Berg, his granddaughters Angela and Alyssa Linvill, and his great grandson Sato Ramsaran.

This tribute owes a debt to Andrew Myers’ 2011 obituary of John Linvill, portions of which are included above.