Martin

E. Hellman

Work on

Technology, War & Peace

This page is also available

in Romanian

courtesy of Alexandra Seremina of azoft,

and

in German courtesy of Anastasiya Romanova of Uhrenstore GmbH.

Technology has given us

powers that were traditionally reserved for gods: raising the dead, creating

new life forms, and destroying the world. As the Mid East, Rwanda, and Enron

demonstrate, humanity's social progress is far from god-like. This chasm between

our technological development, on the one hand, and our social development,

on the other, has created a recipe for disaster that demands urgent attention

if the human race is to survive.

This truth escaped me during

the early years of my career, when I focused on developing technology without

much concern for the consequences. But, during the 1980's, a sequence of events

forced me to face these issues and, from 1982-88, working with the Beyond War

Foundation was central to my life. In that time, the nuclear threat was the

most visible symptom of the chasm demanding our attention, and was therefore

the best vehicle for engaging people in a way that might then extend to other,

pressing issues.

While my initial motivating

force was deeply personal, international events soon took charge. When Ronald

Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981, he brought the nuclear threat into sharp

focus. Whereas previous presidents had anesthetized the American people with

implied assurances that these awesome weapons would never be used, President

Reagan openly discussed nuclear war fighting plans, pushed for the rapid deployment

of "Euromissiles", and developed the Strategic Defense Initiative,

also known as "Star Wars", to protect the U.S. during a nuclear war.

His honesty, while shocking to some, was a blessing that stirred me and many

others into action. And his policies were not that great a deviation from the

past: While he had initiated the SDI, Reagan had inherited the Euromissile deployment

and nuclear war fighting plans from Jimmy Carter, who later received the 2002

Nobel Peace Prize!

As I worked with Beyond

War in an effort to defuse the nuclear threat, we came to the startling conclusion

that any long-term solution required going beyond nuclear arms control, beyond

even the seemingly Utopian goal of complete nuclear disarmament, to what we

came to call "a world beyond war." War would be a thing of the past,

looked on with the same puzzlement and repugnance with which we now view human

slavery.

Ending war had been an unrealistic

dream of mankind for ages. What had changed to make me think it was now possible?

I became convinced that the rapid proliferation of weapons of mass destruction

had made war incompatible with human survival. If the human tendency to make

war is likened to an immovable object, then the survival drive can be seen as

an irresistible force. Which will win out in this cosmic tug of war cannot be

predicted but the new part of the equation, survival depending on ending war,

gives hope that was not present until very recently. With that preface, here

is an overly succinct summary of the reasoning:

- As long as nuclear nations

fear conventional war, they will never eliminate their nuclear arsenals. During

the Cold War, the US was unwilling to agree to a "no first

use" policy when faced with what appeared to be an overwhelming Soviet

advantage in conventional weaponry and manpower. Today, the tables are reversed,

and the Russians have retracted their support for such a policy.

- As weapons of mass destruction

proliferate to ever more nations, the nuclear equation becomes more complex

and dangerous. Non-nuclear nations that fear confrontation with

stronger powers will be strongly motivated to develop nuclear arsenals.

- The most likely trigger

for a nuclear war is a small war or confrontation that spirals out of control,

with the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis being a prime example. Just as World War

I was sparked by a terrorist act in a third world hot spot, big wars often

start from small acts of violence. Every small war is therefore like pulling the trigger

in a global version of Russian roulette. Playing this game once is dangerous,

but engaging in it continually leads to certain death.

- Ending war is impossible

in the current environment, but can become possible via a process of change.

Ending slavery was impossible in the America of 1787, when it was written

into our Constitution, but became a reality within eighty years through a

process involving a sequence of steps. The later steps would have been

laughed at as impossible in 1787, but became possible in the changed

environment produced by earlier steps. Today's

rapid means of communication might hopefully shorten the process considerably.

- During the process of

change, we must simultaneously hold to the long range vision while dealing

with the realities of a very dangerous world. Unilateral disarmament is not

the answer, but unilateral initiative is essential.

As we worked to educate

on the tectonic shift in thinking required for human survival, many Americans

complained, "We can debate our nation's policies and try to change them.

But what about the Russians?" As my wife, Dorothie, and I heard this question

over and over, we thought we might have an answer.

In the 1970's, when Soviet-American

relations had temporarily warmed, we were fortunate to have developed strong

friendships with a number of Russian information theorists we had met through

international symposia and exchange programs. In some cases, these friendships

had led to honest political dialog, free of national rhetoric and propaganda.

If we could bring this experience to more Americans, we hoped Americans would

stop asking "What about the Russians?" and start asking "What

about us? What can we do?"

When Dorothie and I first visited Moscow on this quest in 1984, we knew that

our ultimate goal was unachievable, and focused initially on much more limited aims.

The honest discussions we had had with our Russian friends had

always been one-on-one, out of earshot of other Russians and possibly hidden

microphones. Strict censorship was the law of their land. There was no way we

could bring our experience to a large number of Americans. But, God seems

to reward fools and, in hindsight, this turned out to be precisely the right time

to start such a project.

The

forces of perestroika and glasnost (reform and openness) that

would bring Gorbachev to power in 1985 and lift censorship in 1986 were already

at work behind the scenes during our first visit. Although neither we nor anyone

else in the outside world was aware of it, the scientists we met in 1984 were

actively engaged in that process and, when Gorbachev came to power, several

of them advised him directly. Suddenly, Dorothie's and my dream of "bringing

our experience to a larger American audience" was possible. And, in the

intervening two years, Beyond War had laid the foundation for doing that in

a most effective way. Paradoxically, if we had waited until the project made

sense, it would have been too late since it took time to build trust and

understanding. I can take no credit for the brilliance

of that early move and thank the muse of the fools who seems to whisper in my

ear frequently. Most of her suggestions do not work out so well, but the occasional

home run is worth a number of foul balls. Another major "fool home run"

in my life was working on cryptography in the early

70's when virtually all my colleagues told me I was crazy to do so.

The Beyond War Foundation

supported and expanded our initial overture, culminating in a book, Breakthrough:

Emerging New Thinking, published simultaneously in Russian and English

late in 1987. The

Soviet sponsor was a committee within its Academy of Sciences, headed by Evgeni

Velikhov, then Gorbachev's chief science advisor.

One of the key elements was

to move beyond blame. The Soviet Union and the United States had each focused

on the misdeeds of the other, while largely ignoring their own — where they

have power to effect change. In Breakthrough,

we saw the need for change as a universal. Thus, we talked about the need for

changing the Soviet policy on Afghanistan and the US policy in Central

America, both of which were too dangerous in a world with 50,000 nuclear weapons.

Our hope was that each nation would focus more on its own actions, where it

had the ability to effect direct change, rather than vainly demanding change

from its perceived enemy.

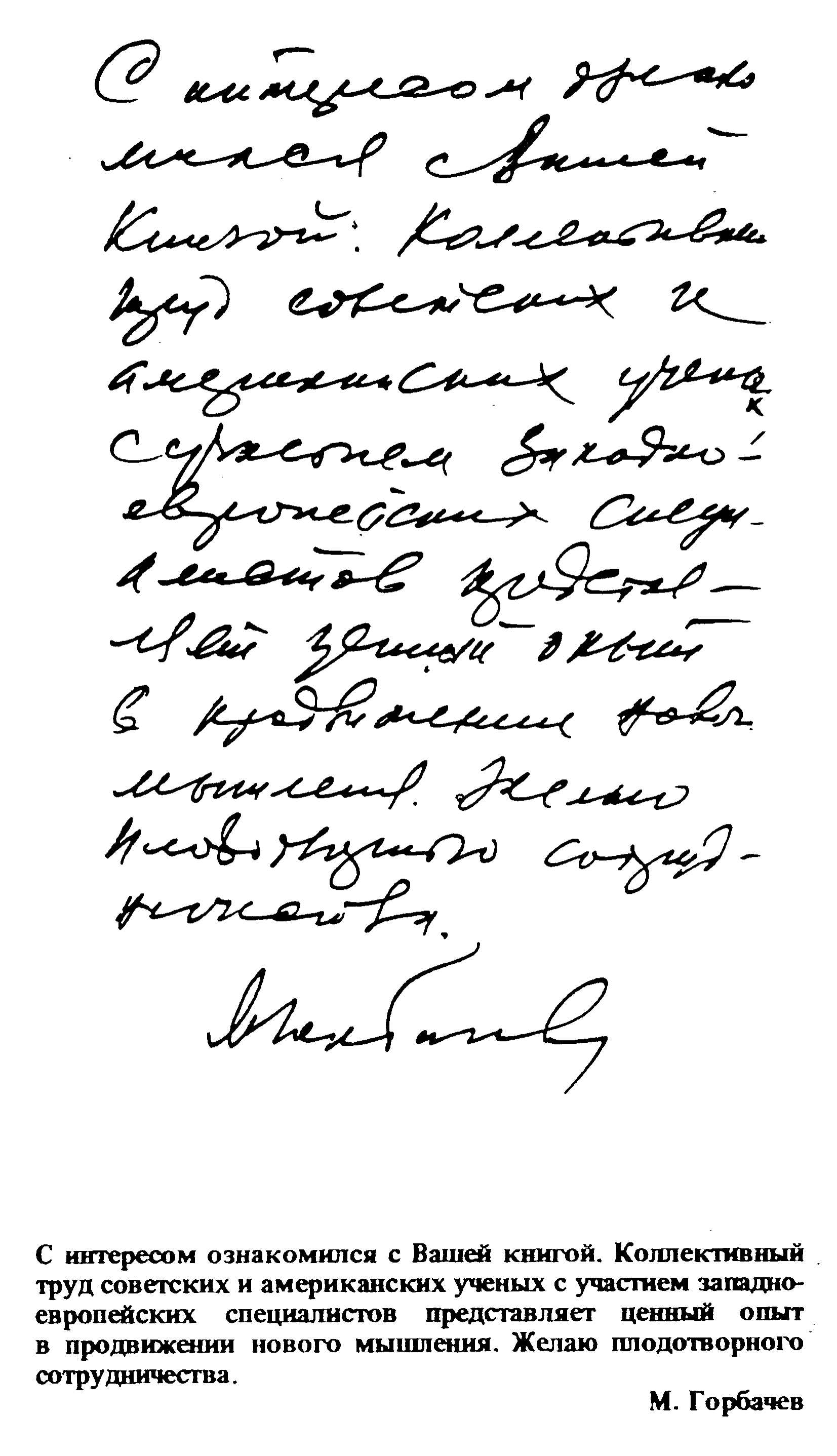

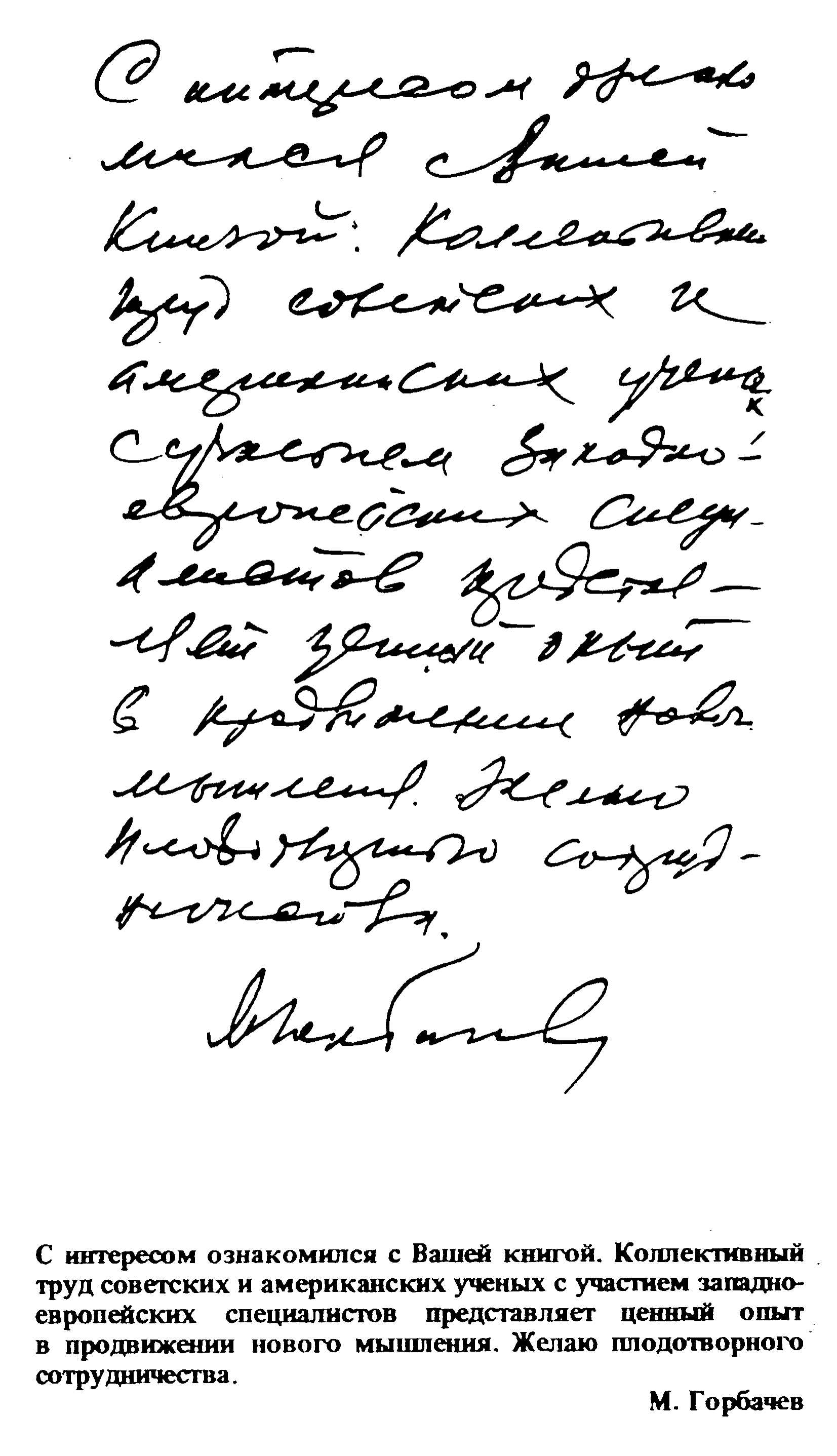

We were gratified that the

book received the following endorsement from President Gorbachev:

The

English translation is:

The

English translation is:

"I have examined

your book with interest. This collective work of Soviet and American scientists,

with participation of Western European experts, represents a valuable experience

in the promotion of new thinking. I wish you a fruitful cooperation."

M. Gorbachev.

For those interested in

exploring the ideas more fully, the full text of Breakthrough is

available on line.

Should you follow that

link, it helps to remember that the book was written at a time when the Soviet-American

nuclear confrontation was the primary, immediate danger facing the world.

Today, when Russia and America are often allied in a war against terrorism,

I should re-emphasize that Beyond War advocated unilateral initiative, not

unilateral disarmament. In its current state, the world is far too dangerous

a place for the latter.

My current effort in this

area, Defusing the Nuclear Threat, builds

on a simple, but overlooked observation:

You have a right to know

the risk of locating a nuclear power plant near your home and to object if

you feel that risk is too high. Similarly, you should have a right to know

know the risk of relying on nuclear weapons for our national security and

to object if you feel that risk is too high. But almost no effort has gone

into estimating that risk. To remedy that lack of information, this effort

urgently calls for in-depth studies of the risk associated with nuclear deterrence.

While this new project

may seem to have a much more modest goal than Beyond War, there is tremendous

hidden potential: My preliminary analysis indicates that the risk from relying

on nuclear weapons is thousands of times greater than is prudent. If the results

of the proposed

studies are anywhere near my preliminary estimate, those studies then become merely

the first step in a long-term process of risk reduction. Because many later

steps in that process seem impossible from our current vantage point, it is better to

leave them to be discovered as the process unfolds, thereby removing objections

that the effort is not rooted in reality.

Return to

home page.

The

English translation is:

The

English translation is: